Australian wine buyers have a lot to think about. I feel for them. Selecting a wine to drink has never been more complex. Online or offline, they’re faced with a barrage of information sufficient to confuse a PhD student. Has it won a gold medal? Or perchance a trophy? Is it rated close to the perfect score? Where does it come from? Does it claim to be organic? Or even biodynamic? Or, if you’re so inclined, natural? How about its maker – is he or she young or old? Trendy, hip or else claiming five generations of traditional heritage? Or all of the above? Is the wine from a single region, a single site, a single plot, or even a single row? It’s a wonder anyone has the clarity to buy a wine at all…

Just when you thought it was confusing enough, here’s another question: did it come from old vines? Well, if it’s French and you see the words ‘Vielles Vignes’ on its label, or if indeed it’s German or Austrian and bears the tag ‘Alte Reben’, or indeed if it’s Australian and its label says ‘Old Vines’, you’re within your rights to assume the affirmative.

So what? Well, that’s the reason I’m writing this piece.

A surprising outcome for Australia…

Commonsense would suggest that it’s the many wine-producing regions of Europe – which commenced making wine either due to or prior to the Roman Empire – that would represent the global hub of old vine vineyards, especially of the most important grapes for modern wine production. In this case, however, history trumps commonsense. For a significant number of these varieties, that hub is indeed Australia. How about that!

Yes, many of the oldest vines in the world are indeed found here, on the planet’s oldest soils, above the oldest rocks. A sweet thought for us, but perhaps an annoying one for others.

How did it happen? Does it give us an edge? And if so, how can we exploit it? And what the heck is an old vine, anyway?

For the sake of clarity, I need to define the scope of this piece. There are isolated regions in many European countries (such as Toro in Spain) and others that border Europe that boast significant plantings of old vines. For the purposes of brevity and relevance I’m focusing more on the wines that are either made here or are a regular part of the broad spectrum of wines that are imported into this market.

What, exactly, is an old vine?

There’s no internationally accepted answer to this question. Broadly speaking, countries with less old vine vineyards and which have been in the habit of uprooting them every 35 or so years don’t have many vines over that age, so they typically describe an old vine as anything aged 35 years or more. For instance, in Spain’s Rioja Alavesa region alone, there are around 6,000 ha of wines that would be classified on this basis as ‘old’.

A little more clarity was applied in November 2024 by the OIV (General Assembly of the International Organisation of Vine & Wine) when it formally declared that an old grapevine must have a minimum of 35 years of age, or if a grafted vine, that ‘the graft connection between rootstock and scion should have been undisturbed for at least 35 years’. To be named as an old vineyard, a planting needs to have at least 85% of old vines. Following this definition, there are old vines in South Africa, the US, France, Italy, Germany, Greece, Armenia and Lebanon. And here, of course!

It’s the Barossa Valley, in all likelihood the world’s most valuable resource of old vine plantings of significant varieties, that we see what I believe is the planet’s most sophisticated classification for old vines. Here, the Old Vine Charter defines four designations for old vine plantings, being: ‘Old Vine’ (35 years or more), ‘Survivor’ (70 years or more), ‘Centenarian’ (100 years or more) and ‘Ancestor’ (125 years or more).

By compiling data provided by Barossa Australia, here is a summary by area of the four levels of the classification. By importance the key varieties are shiraz, grenache, mourvèdre/mataro, cabernet sauvignon, riesling, semillon and chardonnay.

These Ancestor Vine vineyards include:

- Langmeil’s The Freedom Shiraz (1843)

- Turkey Flat’s The Ancestor Shiraz (1847)

- Cirillo Estate’s Grenache (1850)

- Hewitson’s Old Garden Mourvèdre (Koch Family Pilgrim Vineyard) (1853)

- Henschke’s Hill of Grace Shiraz (1860 oldest vines)

- Poonawatta Estate’s The 1880 Shiraz (1880)

- Penfolds’s Block 42 Cabernet Sauvignon (1882 approx.)

Other very old Australian commercial vineyards still in current production include:

- Tahbilk’s 1860 Vines Shiraz (1860) (Nagambie Lakes)

- Tyrrell’s Stevens Old Patch Shiraz (1867) (Hunter Valley)

- Best’s Old Vine Pinot Meunier (1868) Great Western)

- Tyrrell’s 4 Acres Vineyard Shiraz (1879) (Hunter Valley)

In other words, while we have complied with the rest of the world by accepting the 35-year qualification, down here we really don’t consider a vine to be ‘old’ until it’s around 70 years of age or more. The reason is obvious: we just have too many vineyards in current and commercial production that are well over a hundred years old (some of which are more than 150 years old) to take the 35-year concept seriously.

Why does Australia have so many old vine plantings?

It was during the 1830s and 1840s that the then-fledgling Australian wine industry started to build critical mass, which involved the importing of many cuttings from Europe, from a diversity of regions – and a number of varieties. Consequently, our oldest vineyards still currently producing commercial crops for winemaking date back to the 1840s and 1850s.

South Australia dodges the bullet and now dominates the old vine landscape

European wine was nearly wiped out by the vine root-aphid, phylloxera vastatrix, which was taken from North America to Europe in the early 1860s. Having affected the south of France by 1863, it had moved to the vineyards of Bordeaux and Portugal by 1868. A disease caused by a pest had which evolved together with the very different – and resistant – North American vine species, phylloxera caused the replanting of all but the most remote of Europe’s vineyards onto resistant American rootstocks – the only response that certainly works.

Phylloxera checked into Australian shores around 1875, landing at Fyansford near Geelong. By 1877, it had moved from Geelong to Bendigo, leaving a path of viticultural destruction in its wake. It moved through central Victoria, heading towards Rutherglen in the State’s northeast. All attempts to block it were in vain. At this time Victoria was Australia’s major wine-producing state. However, the South Australian government imposed a quarantine on incoming grapevine material, and in doing so managed to escape the dreaded aphid. That’s why this State dominates the Australian wine industry. Its old vine vineyards dodged the phylloxera bullet.

Elsewhere around the world, the inaccessible topography or geographical isolation of some sites and regions helped them avoid the disease entirely (as indeed did the Yarra Valley until relatively recently). Others planted on volcanic or predominantly sandy soil – believed to reduce the impact of the disease – have managed to survive until today.

A different approach to vineyard management in Europe

In a practice still current through much of Europe’s traditional wine regions, vines are uprooted once they reach an age of around 30-35 years because around this age their crop begins to diminish. This is a commercial decision also takes into account the four to five years a young vine takes to deliver a full crop, as well as the additional five years or so before its quality becomes that of a mature vine.

While Australian vineyards are indeed replaced if disease has reduced yields and quality, this has never become a commonplace approach here. Provided a vineyard can compensate for a lower yield with something else, its vines are typically allowed – and even encouraged – to survive. Given the favourably warm, dry conditions of most old vine Australian wine regions the risk of disease is relatively low, although most such vineyards are constantly engaged in an arm wrestle against a couple of fungal diseases that slowly reduce yield by killing off the vine’s wood and structure. Eutypa spreads through large pruning wounds to causes dieback in the arms of older vines, causing the vine to slowly rot away. Phomopsis viticola (dead arm) slowly causes the weakening and breaking of canes, leaving an arm of the vine to die. Viticulturists then decide when the merits of the highly concentrated, high-quality crops produced by such vines shrink to such a level they need to be individually replaced.

What’s so special about the wines from old vines that justifies their age and low crops?

Being less vigorous than their younger counterparts, old grapevines are typically pruned so they have a lower number of buds from which to produce their crops. Smaller crops typically ripen earlier and in cooler seasons are more likely to achieve full flavour and phenolic ripeness. The deep and extensive root systems of old vines also act as an insurance in warmer, drier seasons, as the roots extend deep into lower soils and rocks to extract moisture and nutrition. If you compare the juice and wine from old vines to that from younger, it’s commonplace to observe more intense aromas and concentrated flavours, a superior extract (tannins in reds). There’s a unique way in which flavour drives down the palate that young vine wines cannot deliver, and old vines often deliver the sought-after velvet-like tannin structure in red wines. It’s quite probable that the astonishing depth of their root system contributes towards the higher, rarer levels of complexity in their wines.

Are wines made from old vines necessarily better than wines from younger vines?

Absolutely not, since the same quality empiricals apply, no matter the age of the vines. A high-level wine still needs to come from well-managed high-quality sites, from a good season (in most cases) and needs to be made to a high level of competence regardless of vine age. Just because it comes from old vines does not guarantee a good wine.

Other reasons to treasure our old vines

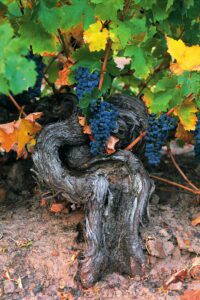

Aside from the astonishing sight presented by gnarly, twisted rows of ancient vines – either trellised or cultivated as bush vines – and the sheer fascination that a plant of such age can retain its relevance and personality as a valuable component in a commercial process, they also represent an astonishing pool of genetic material. In fact, the very best that humankind had selected from noble varieties for many centuries.

Unlike the modern trend of diving deep into the genetic weeds by planting precise and carefully bred individual clones of varieties, these arrived here as mass selections, containing a multiplicity of clones, each with their own unique characteristics. It’s also accepted that the genetic diversity of our old vine plantings contributes massively to the complexity and character of their wines.

The Nursery Block planted in 1866 by Henry Best in Great Western, Victoria, is perhaps the world’s largest single resource of pre-phylloxera grapevine genetic material. It contains 32 different varieties, presumably a multitude of clones of each.

With several major varieties, as we have seen, Australia has the potential to look deep into this resource, which many consider to be significantly superior to the genetic material with which Europe and the rest of the wine world affected by it was replanted after phylloxera. It’s highly likely that we could discover natural genetic means to enhance disease resistance, drought tolerance and fruit quality.

Should we feel a sense of responsibility to look after our old vines?

Australia’s ancient vineyards are a global treasure and as such should receive the very highest levels of respect and care. Back in the 1980s, when demand for South Australian wine was so poor you could buy Barossa shiraz in muffins, a vine pull scheme implemented by the South Australian government – and encouraged by much of the industry at the time – robbed us of much of this scarce and diminishing resource. This kind of idiocy must never happen again.

To be fair, our industry, led in no small part by Barossa Australia, is today totally awake to the value and importance of this resource. There’s a greater emphasis on old vines in the packaging, marketing and indeed pricing of wines from these special vineyards which the market has supported.

At a time in which Australian wine is struggling to articulate its identity – both locally and on the world stage – one might suggest that we need to make the most of something we have that others lack. Are we doing all that we could to drive home the message that not only does Australia boast the world’s oldest rocks and its oldest soils, but also its oldest vines from which it creates some of its finest and most identifiably Australian wines? Or that many of our vineyards across our finest regions are planted from selections from this genetic material?

Go and check out one of these unique vineyards. It might change the way you think about wine and your concept of where Australia fits on the world stage.

This article was first published in Selector magazine, issue 93.