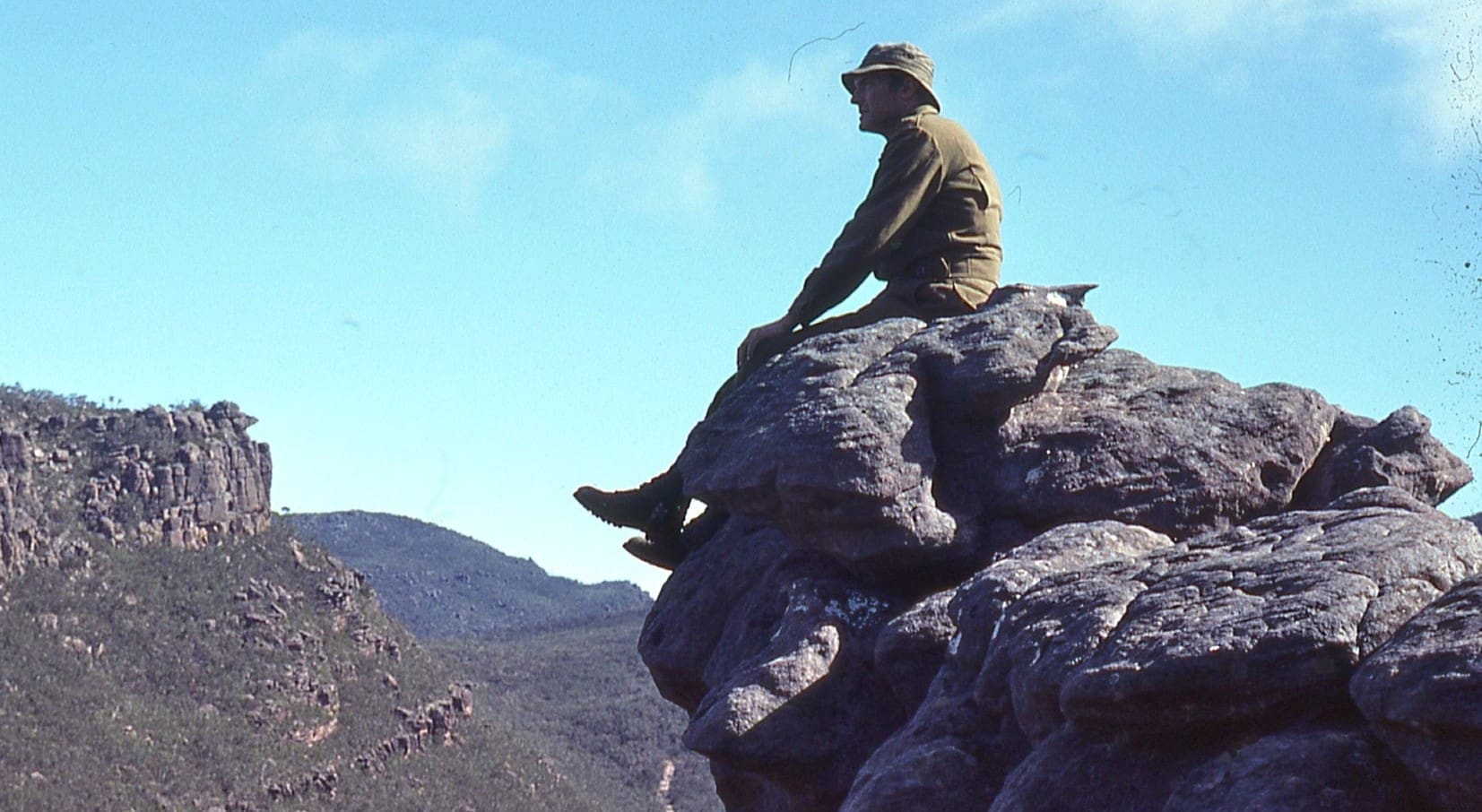

Rather a long time ago it dawned on me that I chose my father wisely. Rodney Oliver, my Dad, was the Chaplain at Ballarat Grammar School throughout the 1960s, where he also taught Latin and English. He was also proficient in Hebrew and Sanskrit. As much an outdoors guy, he looked after the school’s unusually large Queen Scouts troupe during which he encouraged or otherwise provoked those in his charge to ascend or descend large natural obstacles that would leave most of humanity in abject terror. Hospitalisations after climbing and trekking through the Grampians were but rare, and records suggest that all children did indeed return either to the safety of their parents’ homes or the boarding house.

My first memory of my father was to see him perched atop the pitched roof of the school chapel with a paintbrush in one hand and a tin of paint in the other. No scaffolding or safety rope in sight; just a wooden ladder.

It was difficult for Dad and the other teachers to buy decent bottled wine in Ballarat during the 1960s. They overcame this by purchasing full barrels from makers like Morris, Birk’s Wendouree and Osicka’s which they would collect at the local railway station. A bottling party would ensue and that wine which actually made its way into glass would sustain the staff until the next barrel arrived. They’d burn some sulphur paper in the empty cask before sealing it and sending it back by train to the winery.

My earliest memories of wine involved weekends. Some Saturdays my father would pile my brothers and Lesley, my mother, into the old VW microbus and off we’d head towards Tahbilk or Osicka’s. I remember less about the taste of wine than a fascination with different wine labels – why some labels went on some bottles but not on others. Years later I came to understand why these winery visits would take so long.

Into the early ‘70s, by which time Dad had become a parish priest. Come Sundays our dining table would be extended for a large number of guests – my mother was a natural host – and wine would be a central prop to the lunch and surrounding conversation. I’d hang around just long enough to be polite before heading out for whatever sport was in season, but also for long enough to appreciate the simple, humble and spiritual role that serving wine around a table could play in a family and within a community.

Dad was a wine enthusiast, not an expert. Keen to learn about soils and techniques – he’d describe himself as a ‘National Geographic scientist’. His wine conversation was confident and entertaining, if not always correct, as I later found. And he was never afraid to let you know if he particularly appreciated the contents of the glass in front of him, displaying the kind of awestruck expression more normally observed in places like the Louvre or the Sistene Chapel.

Keen to learn and experience more of wine’s diversity, he was my willing accomplice in day-night-long incursions to the string of Expovin wine events held in Melbourne during the early 1980s. Back then I was studying Agricultural Science at Melbourne University while Dad, conveniently, was Chaplain at Trinity College, where the family occupied rather a large stone house and surrounding garden. Each of us armed to the teeth on arrival with a fresh baguette, we’d efficiently work through all our tasting vouchers, only then to be topped up by people like Di Cullen and Doug Bowen. We never ran out. And with Dad being a tall and rather distinguished looking rooster, we were always poured more than a decent shot of auslese by the frauleins operating the German-looking businesses that largely sold wine from Austria.

Occasionally, Dad would attempt to sing on the walk back from the Exhibition Buildings, but that’s when I’d remind him that if he actually had a singing voice (he was terrible) he’d already be Archbishop.

Always prepared to see the good in people and wine, but perhaps a better judge of people, Dad taught me by example that wine was a gift and it was for sharing. He loved the connection between wine and its place of origin and treasured those who grew and made it. While my Mum was perhaps a little perplexed that I chose not to use my agriculture degree to solve the food problems of a starving planet, Dad experienced no such pang. Like a magician, he would always find space to store box after box of topped-up bottles of the best wines from my tastings. And yes, Mum followed suit, shortly after.

Perpetually fascinated by language, Dad was always keen to expand my professional vocabulary, especially with words that were eccentric, obsolete or both. Did you know that the word ‘smellfeast’ means a member of a drinking group? He did. That a ‘shotdog’ is a companion tolerated only because he or she is paying for the drinks? He did. Or that if you’re one of those people to whom drink inspires courage, you’re a ‘potvaliant’. Ditto.

Jeremy Muller, the owner of Peccavi Estate, once told me he needed a name for his second label. ‘Peccavi’ is Latin for ‘I have sinned’. The answer came a day later from Dad – by now an Archdeacon in the Anglican Church: ‘No Regrets’. If only Dad had lived long enough to see that for a few years this became a popular brand in several Chinese cities as a wine for weddings. He’d have collapsed laughing.

While never really teaching me anything technical about wine, Dad taught me the other important things. Wine is to be respected. It’s to be shared. We all have our own perspectives on it, and these can be quite different. You don’t need to be an expert to have an opinion, but if you’re curious about it the learning journey can be fascinating. Like the food we eat, wine is from the earth and as such should be celebrated. And, to paraphrase rather a lot, Jesus was both familiar with and fond of wine and its place around a table. From time to time, Dad would remind some of the famous wine-related stunt that Christ pulled off at a wedding reception.

If there’s a most significant reason why I do what I do, that reason is my father. It’s no accident that the present given to Dad by the parish of Dandenong after his ten year-stint as their Vicar was a beautifully crafted small oak barrel that’s now sitting a few metres from where I’m writing, just off to the left. Thanks to winemaker Nigel Dolan, I had it filled with exceptional pre-phylloxera Barossa port and for the last thirty years and more I’ve topped it up with love and care. Dad adored his barrel and to this day its contents remain rather special. Every time I pour a glass I see his smile. It remains our ongoing connection.