Why do Australian winemakers keep trying to re-invent wine and its culture? It’s hard to believe the cause is our historic isolation from much of the world because international travel is cheap these days and communication is instant. What then explains the ever-widening gap between how our makers go about creating wine and the approach taken by the rest of the world?

I’ve written elsewhere that too many Australian winemakers have lost their mojo. By this I mean that they appear unable and unwilling to determine their own styles and to accept and learn from the consequences of their own decisions. The conviction of individual winemakers, based on ability, science, history and an understanding of world wine, has led to the creation of world-class classics such as Giaconda Chardonnay, Mount Mary Quintet, Grosset Polish Hill and Neldner Road Kraehe Shiraz. However, that individual conviction has been replaced to an excessive extent by a groupthink approach that has dumbed down and diminished our quality.

Follow the leader

What do you seek when you travel and taste your way through the world’s great wine regions? How would you react if all the nebbiolo in the region of Barolo tasted the same? Or all the riesling on the slopes of the Mosel? Or even all the grenache in McLaren Vale? I’d take up knitting.

Yet, listen to Australian winemakers talk and you will hear phrases like: ‘This is the style of chardonnay (substitute any variety) that the Yarra Valley (substitute any region) should make and this is the way to do it’. Examples? It’s clearly been decided that cool-climate pinot noir and shiraz just have to be fermented with a high percentage of stalks, even if the stalks involved are sappy and yet to lignify. Similarly, chardonnay needs to be fermented and matured in large format oak. Or at least partially in something ceramic or made from concrete. As if there’s a single solution for all vineyards in a region!

We went through something similar in the late ‘70s and ‘80s when cabernet had to be so green you could roll a lawnmower over it. Popular winemaking wisdom in the ‘90s was that you shouldn’t filter pinot so, to emphasise their unfiltered nature, pinots were bottled with varying levels of haziness. While it might have given microbiologists something to think about, it just didn’t work. History is always repeating. In Australia, especially.

South Australian grenache now apparently needs to be lean, green and acidic. Makers are talking about it as if it’s cool climate pinot noir, which suggests an understanding of neither. Far too many such wines are afflicted by the same spectre of whole bunch fermentation that has ruined so many pinots and shirazes in my home state of Victoria.

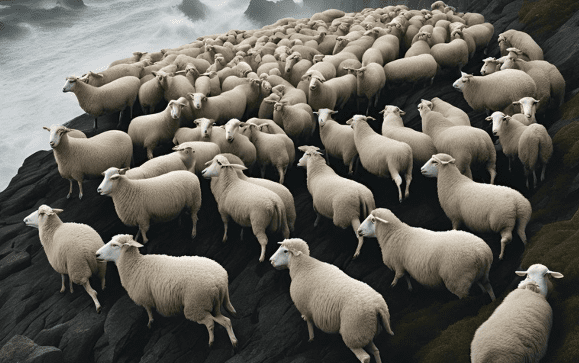

For a decade and more it’s been obvious that too many Australian winemakers move as a collective, or a pack. And like most collectives or packs, there’s usually a leader involved whose job it is to ensure the group is headed the right way and that those who drift away from the chosen path are quickly corrected. Or culled. Similarly, dissident judges in wine shows with different opinions regarding style and quality are rarely invited back.

While winemaking groupthink certainly has a place with commercial wines that deliver flavour, style and quality for an affordable price, it shouldn’t play a role at the sharp end of the market, which is where most of the makers in our premium regions seek to compete.

There’s a boring sameness and homogeneity about too many aspirational Australian wines that robs them of character and their sense of place. There is a dumbing down of innate ability of talented winemakers to create and refine their own personal imprint of style. There’s a dominant ‘one size fits all’ approach and those who do their own thing are seen as black sheep by the rest of the pack.

Why groupthink is wrong for premium wine

Winemakers will never make great wine by doing the same things as the guy or gal over the fence. Too many variables are involved. Yet too many Australian winemakers engage in a perpetual routine of follow-the-leader, believing it’s the only way to the top. Across our best regions too many collectively obsess over what their key varieties should all taste like and the techniques they all need to adopt to ensure they all do. Yet, in the very next breath, they will talk up the idea of making wines that ‘express their site’ or ‘terroir’, seemingly unaware of the massive contradiction involved.

Groupthink is diametrically opposed to the concept of making premium wine. It dumbs down the ability of special sites to reflect their unique characters and for regions to express their key identifying characteristics. Winemakers are less able to fashion wines that reflect their own convictions around style and quality. The concept of house style – which is understood and celebrated in the world of premium wine – is lobotomised. Too many famous names in Australian wine are currently releasing wines that are both significantly different and significantly inferior to those upon which they built their reputations.

Wine regions rarely have a single homogeneous soil type, exposure or aspect. History and science both confirm that the deeper you study such things, the more that small differences will emerge – each of which do impact on the finished wine. Even in Coonawarra, which to most observers offers the topographical appeal of a billiard table, there are ultra-subtle differences in elevation and soil type that massively impact on wine structure and ripening time. The collective of elevated seabeds that is Burgundy constitute the most highly analysed and classified piece of agricultural land on the planet. The massive differences between the quality and characteristics of its vineyards – over what might seem to the uninitiated as absurdly small distances – do indeed impact massively on style and quality. This becomes obvious when you taste wines made pretty well the same way at those Burgundian domaines or negociants with access to a diversity of vineyard sites throughout the region. It’s self-evident that it’s the site that talks the most. And that’s what we celebrate.

The deep lack of conviction amongst those driving the groupthink is evidenced by the massive and rapid swings of the style pendulum from one end to the other. There are now even welcome signs that they’re returning flavour to the very chardonnays that have been stripped of it for more than a decade.

I was recently told by one high-profile Yarra Valley chardonnay maker that having spent the last decade and more refining how to deliver the taut shape, acidity and mineral nature of the wine he has become famous for, he has since recognised that he’s gone too far and stripped out too much fruit in the process. So now he wants to return fruit ripeness and flavour to his framework of acidity and minerality to improve the wine. I wonder if, given this admission, he will return the trophies and awards he has collected over the last 15 years for wines that were stripped of flavour and almost dangerously acidic?

My fear, based on forty years of professional observation, is that we’ll only climb out of this rabbit hole to dive straight down another. That is our recent history.

People make great wine, not recipes

I’ve written elsewhere about the importance of the human being in the making of great wine. You can have the right place, the right equipment and the right brand, but that’s far from any guarantee that the wine will deliver greatness. The human factor is essential – be it the owner, the winemaker or both at the same time. Whoever this person is, he or she requires a deep understanding of the very nature of the wine being grown and made, and how it sits in the global environment. Yes, sometimes a brand or a vineyard will deliver something truly astonishing, but the concept of greatness requires the kind of consistency that can only result from this level of knowledge.

It’s also essential that all those involved in the entire process have a deep love and drive for what they’re trying to achieve, in everything from the smallest of tasks in the vineyard to the fine-tuning of blends. You can hide some deficiencies in lower-priced to mid-market wine, but not at the sharp, pointy end of quality.

Don’t disrespect a house style that works

Let’s return to the concept of individual preference for style, and how it affects winemakers. As I have mentioned, this is not a game for those without strong feelings or passions for style. Furthermore, in the game of making great wine, a winemaker should aspire to have a characteristic stamp or personal style that sets his or her wine apart from those made by others.

Companies and brands should seek to develop their own styles as well – in fact a ‘house style’ is considered around the world as something that might define one great maker from another. Winemakers might come and go from Domaine de la Romanée-Conti, but the house style, as determined by its owner, remains the same. Such styles might result from a particular technique or process, or a combination of several such things. Examples might be the size and format of cooperage, a unique fermentation technique or vessel, or whatever. Some Champagne houses use oak casks to mature base wines, others age reserve wines in magnums. The possibilities, globally, are endless.

All of this flies against the notion of groupthink. In fact, it becomes empirical that the best makers within a region inevitably will craft wines that are utterly distinctive and different from each other. That’s what we find around the world, and the differences between the great makers within regions are admired and celebrated. But not here, apparently…

We’re doing it right and the rest of the world will soon understand…

Too many Australian winemakers have adopted misplaced beliefs as fact. Firstly, too many are convinced that their sites are good enough for them to make wine of international class, but Australian wine is crawling with makers whose quality ambitions far exceeds their sites’ potential. Today, from single sites that might best be described as average, companies now often release a ‘regional’ range, a series of ‘individual vineyard’ wines plus a collection of ‘individual row selection’ wines. There’s hardly any difference in taste or quality between the lot of them – and none of them threaten the upper levels of quality – but of course there are significant differences in price.

Many wine brands would be much more profitable if their owners accepted this reality and started focusing on wines at price points that their customer base actually wants.

Secondly, many are convinced that as makers it’s their role to superimpose over their site whatever style of wine they wish to achieve – which is all too often a sheep-like following of the groupthink approach. Consequently, they forfeit any chance of developing their own style or, if their sites are good enough to express it, their own terroirs. An example? It’s a massive trend in Australia today to harvest fruit before it’s reached flavour ripeness, which instantly removes the resulting wine’s chance of ever expressing site terroir or even regionality. That’s why so many Australian chardonnays, shirazes, grenaches and pinot noirs taste the same.

Thirdly, and buoyed no doubt by their comrades in the groupthink movement, they actually believe it’s only a matter of time before the wines they’re currently making will be accepted by the rest of the world wine market as the new global benchmarks. However, it’s not up to winemakers to decide or declare that their own wines are either the best or second-best on the planet and then to expect the wine world to fall behind in lockstep. Only the market will decide, and the market is a very complex place these days.

Makers of great wines are their own leaders

Of course there’s a place for winemakers and growers to work collegiately and together to build knowledge and deliver a suite of options – technical and stylistic – from which they can choose to suit their own wines – based on their own style ambitions and the empiricals delivered by their sites. Equally, it’s obvious that the more winemakers exchange ideas and concepts that their collective experience stands to benefit most of them, even if this shared experience simply reinforces why some might choose to do things differently from their neighbours.

One of the more understated virtues of great leaders is that they know how and when to be humble. Perhaps our makers, especially those at the head of the groupthink movement, might accept that nobody has ever succeeded by making wine the rest of the world doesn’t really want to drink and then telling them they’re wrong. There’s always room for innovation in wine – just look at how the recent introduction of fruit sorting technology in Australia has improved the species – but you won’t be rated amongst the great makers of the world if you’re not making wine that fit within the globally accepted parameters of what constitutes elite quality.

Time and again Australian makers have shown a willingness to follow trends and fads, which the groupthink approach has only served to magnify and distort. None of these trends have stuck and become established as a long-term part of our wine identity: from the days of the Parkerised shirazes, to the unwooded chardonnay epidemic around the turn of the century, to the once-ubiquitous blend of shiraz and viognier, to the stripped fruit chardonnays and the sappy, vegetal reds lacking fruit ripeness and conviction of today.

Wine trends move faster in Australia than anywhere else, which suggests to me a lack of mojo and conviction. Of course with everyday wine it’s smart business to keep a finger on the consumer pulse, but if you want to play in the big league at the pointy end of quality you have to do more than just follow the leader.

Australia is blessed with a multitude of exceptional sites and a climate that encourages the growing of top-level fruit for winemaking. It is equally blessed with a huge number of individuals with exceptional talent. Maybe it’s now time those individuals with the ability and the resources shook free of the groupthink approach and took a firm hold of their own destinies.

After all, that’s how Rick Kinzbrunner did it with Giaconda, how Jeff Grosset did it with Polish Hill and how Dave Powell did it throughout his journey from Torbreck to Neldner Road…